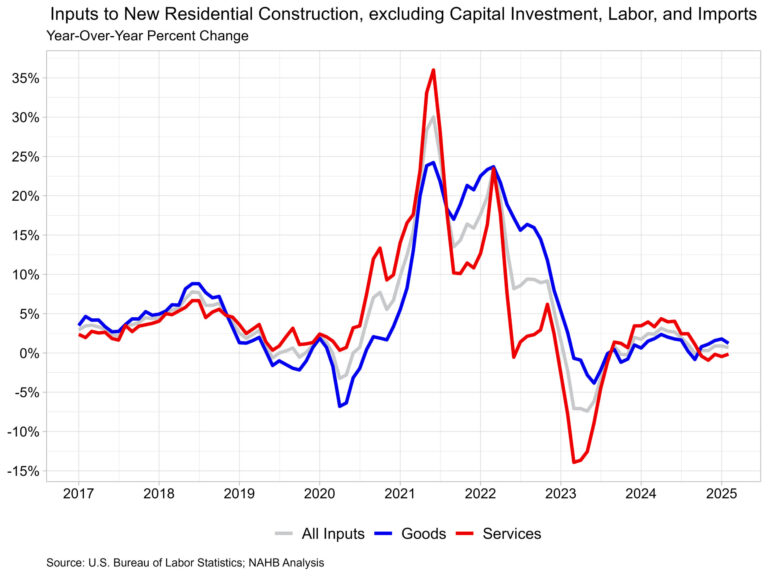

Prices for inputs to new residential construction—excluding capital investment, labor, and imports—were up 0.6% in March according to the most recent Producer Price Index (PPI) report published by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The increase in February was revised upward to 0.7%. The Producer Price Index measures prices that domestic producers receive for their goods and services; this differs from the Consumer Price Index which measures what consumers pay and includes both domestic products as well as imports.

The inputs to the New Residential Construction Price Index grew 1.3% from March of last year. The index can be broken into two components—the goods component also increased 1.3% over the year, with services increasing 1.3% as well. For comparison, the total final demand index, which measures all goods and services across the economy, increased 2.7% over the year, with final demand with respect to goods up 0.9% and final demand for services up 3.6% over the year.

Input Goods

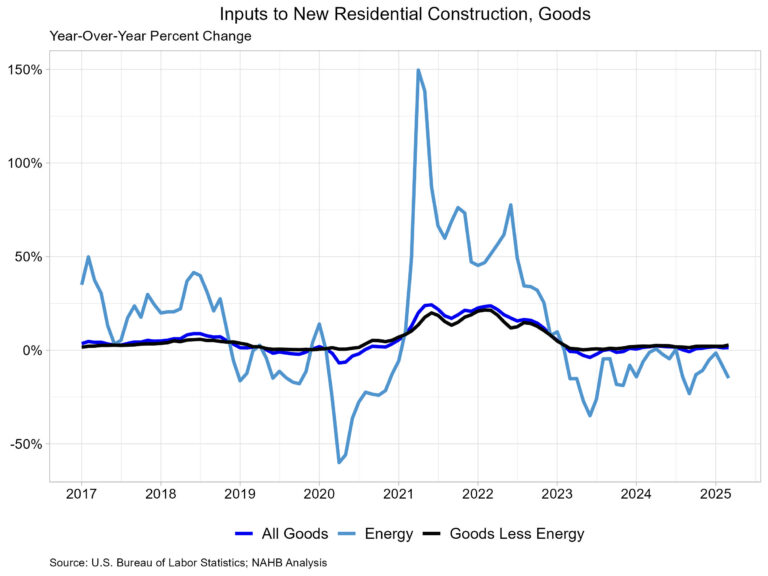

The goods component has a larger importance to the total residential construction inputs price index, representing around 60%. For the month, the price of input goods to new residential construction was up 0.5% in March.

The input goods to residential construction index can be further broken down into two separate components, one measuring energy inputs with the other measuring goods less energy inputs. The latter of these two components simply represents building materials used in residential construction, which makes up around 93% of the goods index.

Energy input prices fell 3.9% between February and March and were 14.9% lower than one year ago. Building material prices were up 0.8% between February and March and up 2.7% compared to one year ago. Energy costs have continued to fall on a year-over-year basis, as this marks the eighth consecutive month of lower input energy costs.

Metal products used in residential construction saw the largest price increases in the month of March. Across all inputs to new residential construction, ornamental and architectural metal work increased the most, up 21.0%. Ornamental and architectural metal work products increased 11.2% on a month-to-month basis, by far their largest monthly increase for the product, with the next closes being 7.9% back in October of 2021.

Input Services

While prices of inputs to residential construction for services were down 0.1% over the year, they were up 1.1% in March from February. The price index for service inputs to residential construction can be broken out into three separate components: a trade services component, a transportation and warehousing services component, and a services excluding trade, transportation and warehousing component (other services). The most significant component is trade services (around 60%), followed by other services (around 29%), and finally transportation and warehousing services (around 11%). The largest component, trade services, was up 0.7% from a year ago. The other services component was up 1.6% over the year. Lastly, prices for transportation and warehousing services advanced 3.6% compared to March last year.

Discover more from Eye On Housing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This article was originally published by a eyeonhousing.org . Read the Original article here. .