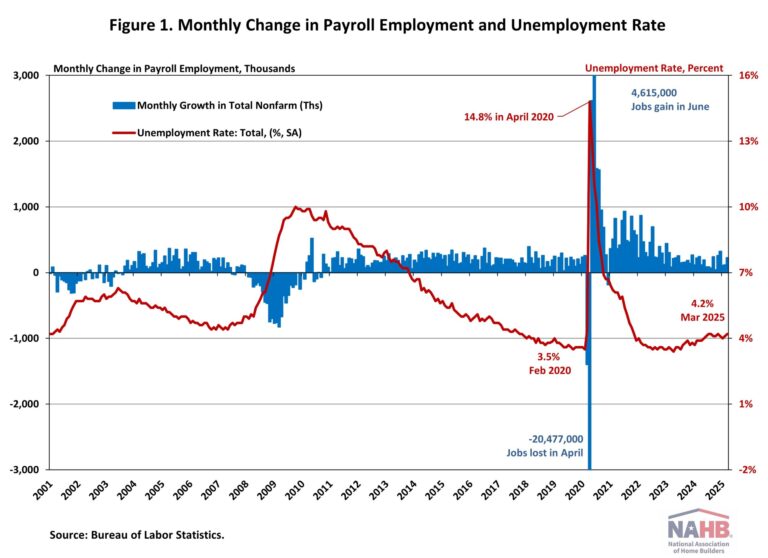

The U.S. job market unexpectedly accelerated in March, while the figures for January and February were revised downward substantially. The unemployment rate ticked up slightly to 4.2% in March, from 4.1% the previous month. This month’s jobs report highlights the continued resilience of the labor market despite sticky inflation, a drop in consumer confidence, mass federal government layoffs, and growing economic uncertainty.

Noticeably, residential construction employment has shown signs of weakness in recent months. In March, the six-month moving average of job gains for residential construction turned negative for the first time since August 2020. It reflects three significant drops in employment: 8,400 jobs in October 2024, 6,700 jobs in January 2025, and 9,800 jobs in March 2025. Additionally, the construction job openings rate has returned to 2019 levels, driven by a slowdown in construction activity.

In March, wage growth slowed. Year-over-year, wages grew at a 3.8% rate, down 0.3 percentage points from a year ago. Wage growth has been outpacing inflation for nearly two years, which typically occurs as productivity increases.

National Employment

According to the Employment Situation Summary reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), total nonfarm payroll employment rose by 228,000 in March, following a downwardly revised increase of 117,000 jobs in February. Since January 2021, the U.S. job market has added jobs for 51 consecutive months, making it the third-longest period of employment expansion on record.

The estimates for the previous two months were revised down. The monthly change in total nonfarm payroll employment for January was revised down by 14,000 from +125,000 to +111,000, while the change for February was revised down by 34,000 from +151,000 to +117,000. Combined, the revisions were 48,000 lower than previously reported.

The unemployment rate rose to 4.2% in March. While the number of employed persons increased by 201,000, the number of unemployed persons increased by 31,000.

Meanwhile, the labor force participation rate—the proportion of the population either looking for a job or already holding a job—rose one percentage point to 62.5%. For people aged between 25 and 54, the participation rate decreased two percentage points to 83.3%. While the overall labor force participation rate remains below its pre-pandemic levels of 63.3% at the beginning of 2020, the rate for people aged between 25 and 54 has been trending down since it peaked at 83.9% last summer.

In March, employment rose in health care (+54,000), social assistance (+24,000), and transportation and warehousing (+23,000). Employment in retail trade also added 24,000 jobs in March, partially reflecting the return of workers from a strike. However, within the government sector, federal government employment saw a decline of 4,000, following a loss of 11,000 jobs in February. The BLS notes that “employees on paid leave or receiving ongoing severance pay are counted as employed in the establishment survey.”

Construction Employment

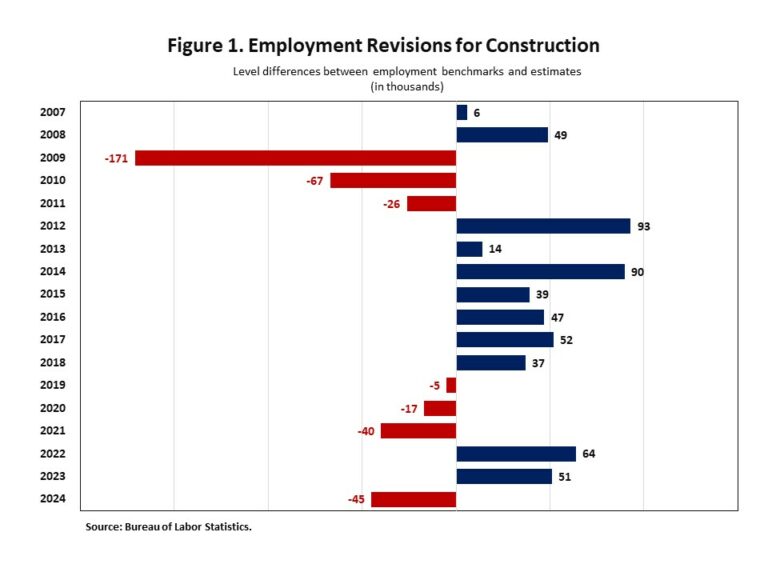

Employment in the overall construction sector increased by 13,000 in March, following a gain of 14,000 in February. While residential construction saw a decline of 9,800 jobs, non-residential construction employment added 22,300 jobs for the month.

Residential construction employment now stands at 3.4 million in March, broken down as 958,000 builders and 2.4 million residential specialty trade contractors. The six-month moving average of job gains for residential construction was -2,883 a month, mainly reflecting the three months’ job loss over the past six months (October 2024, January 2025 and March 2025). Over the last 12 months, home builders and remodelers added 14,000 jobs on a net basis. Since the low point following the Great Recession, residential construction has gained 1,367,600 positions.

In March, the unemployment rate for construction workers declined to 4.3% on a seasonally adjusted basis. The unemployment rate for construction workers has remained at a relatively lower level, after reaching 15.3% in April 2020 due to the housing demand impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Discover more from Eye On Housing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This article was originally published by a eyeonhousing.org . Read the Original article here. .