Manufactured homes play a measurable role in the U.S. housing market by providing an affordable supply option for millions of households. According to the American Housing Survey (AHS), there are 7.2 million occupied manufactured homes in the U.S., representing 5.4% of total occupied housing and a source of affordable housing, in particular, for rural and lower income households.

Often thought of as synonymous to “mobile homes” or “trailers”, manufactured homes are a specific type of factory-built housing that adheres to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD’s) Manufactured Home Construction and Safety Standards code. To qualify, a manufactured home must be a “movable dwelling, 8 feet or more wide and 40 feet or more long”, constructed on a permanent chassis.

The East South Central division (Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi and Tennessee) have the highest concentration of manufactured homes, representing 9.3% of total occupied housing. The Mountain region follows with 8.5%, while the South Atlantic region holds 7.7%.

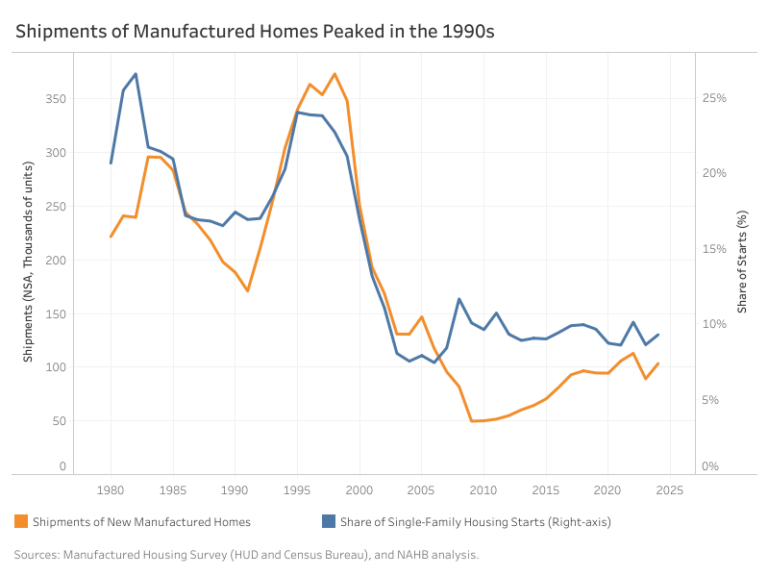

The 1990s saw a surge in manufactured home shipments, peaking in 1998. During this period, manufactured homes constituted 17% to 24% of new single-family homes. However, shipments declined in the early 2000s, coinciding with a rapid increase in site-built housing construction leading up to the 2008 housing crisis. Since then, manufactured homes have stabilized at around 9% to 10% of new housing.

Characteristics of the 2023 Manufactured Home Stock

Given that most manufactured homes were produced in the 1990s, a significant portion of the existing manufactured home stock — approximately 72.2% — was built before 2000. Consequently, 7.7% of these homes are classified as inadequate compared to 5% of all homes nationwide. About 2% are considered severely inadequate and exhibit “major deficiencies, such as exposed wiring, lack of electricity, missing hot or cold running water, or the absence of heating or cooling systems”. However, with proper maintenance, manufactured homes can be as durable as site-built homes.

Currently, 57% of the occupied manufactured homes stock are single-section units, while 43% are multi-sections, according to the AHS. Single-section homes are manufactured homes that can be transported from factory to placement in a single piece while multi-sections are transported in multiple pieces and are joined on site. However, data from the Census show that newer shipments indicate a shift toward multi-section homes.

Most single-section homes are less than 1,000 square feet and contain five total rooms in the house — typically two bedrooms and three bathrooms. In contrast, multi-section homes usually range from 1,000 to 2,000 square feet and have six rooms, comprising three bedrooms and three bathrooms.

Demographics of Manufactured Homes Residents

Manufactured homes serve as a crucial housing option, particularly for those living in rural or non-metro areas. AHS data highlight a stark contrast between the locations of single-family and manufactured home residents. While most manufactured home residents (53%) live in rural areas, single-family residents are mostly concentrated (67%) in urbanized areas — defined as territories with a population of 50,000 or more. In comparison, only 33% of manufactured home residents reside in urbanized areas. Residents of both manufactured and single-family homes are less common in urban clusters — areas with populations between 2,500 and 50,000 — comprising just 13% and 9%, respectively.

The median age of a manufactured home householder is 55, the same as single-family householders. However, most manufactured home householders (37.8%) have an education attainment level of high school completion compared to single-family householders whose largest group (24.8%) have completed a bachelor’s degree.

Income disparities are also significant. The median household income for manufactured home residents is $40,000, far below the $85,000 median income for single-family householders. The gap widens among homeowners, with manufactured homeowners earning a median of $41,500 versus $93,000 for single-family homeowners.

Household CharacteristicManufactured Homes HouseholdSingle-Family HouseholdAge (Median)5555Majority Education Attainment LevelHigh school or equivalency (37.8%)Bachelor’s degree (24.8%)Annual Household Income (Median)$40,000$85,000Annual Household Income of Homeowners (Median)$41,500$93,000Sources: 2023 American Housing Survey (AHS) and NAHB analysis.

Cost of Buying and Owning Manufactured Homes

One of the key advantages of manufactured homes is affordability. The average cost per square foot for a new manufactured home in 2023 was $86.62, compared to $165.94 for a site-built home (excluding land costs) — a difference of $79.32 per square foot. This difference in cost has only grown over the decade from $51.84 per square foot in 2014. For a 1,500-square-foot home, this translates to a savings of approximately $118,980, and this savings has grown despite the average cost of manufactured homes increasing at a higher growth rate of 7.4% CAGR versus 6.1% CAGR for new single-family homes.

Owning a manufactured home is also more affordable in total housing cost, which includes mortgage payments, insurance, taxes, utilities and lot rent. According to the AHS, owners of a single-section manufactured home have a median total monthly housing cost of $563, while the cost for a multi-section home is $805. In contrast, the median monthly cost of owning a single-family home is $1,410.

Despite the lower costs associated with manufactured homes, affordability remains a challenge for many owners. Among single-section manufactured homeowners, 36.6% are considered cost-burdened, meaning they spend 30% or more of their income on housing. This is slightly higher than the 28.4% of multi-section manufactured homeowners and the 27.6% of single-family homeowners facing similar financial strain. This disparity underscores the reality that even though manufactured homes are a more affordable option, lower-income households are still disproportionately burdened by housing costs.

Manufactured Home Pricing

Data on manufactured home appreciation is limited. However, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA) publishes a quarterly house price index for manufactured homes. Comparing the indices for manufactured and site-built homes, manufactured homes have closely followed the appreciation trends of their site-built counterparts. Between the first quarter of 2000 and the last quarter of 2024, the index value for manufactured homes increased by a cumulative 203.7%, slightly surpassing the 200.2% increase for site-built homes. This indicates that the manufactured home markets face much of the same demand opportunities and supply challenges of the broader housing market.

It is important to note that this data reflects only manufactured homes financed through conventional mortgages as real property, acquired by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac (the Enterprises). In contrast, the majority of new manufactured homes are titled as personal property, which is not eligible for conventional mortgage financing because the Enterprises do not acquire chattel loans. Nonetheless, it is common for manufactured homes to be placed on private land even though the unit is under a personal property title — a title that applies to movable assets, such as vehicles, tools or equipment, and furniture, whereas a real estate property title includes land and any structures permanently attached to it.

Despite this distinction, there has been a steady increase in the share of manufactured homes titled as real estate. Since 2014, the percentage of real estate-titled manufactured homes has grown from 13% to 20% in 2023, indicating a positive trend toward greater financial recognition and stability for these homes.

Zoning Restrictions and the Future of Manufactured Homes

Manufactured homes provide a cost-effective housing solution, particularly in rural areas where the transportation and material costs for site-built homes can be significantly higher. However, restrictive zoning laws often limit their placement in urban areas. Regulations such as bans on manufactured home communities and large lot size requirements can substantially increase costs, making it difficult to establish manufactured housing in cities. Reducing these zoning barriers could not only expand affordable housing options in high-cost urban areas but also improve access to essential services such as healthcare and economic opportunities for lower-income communities.

A successful example of zoning reform comes from Jackson, Mississippi, where city officials partnered with the Mississippi Manufactured Housing Association (MMHA) to launch a pilot program highlighting the potential of prefabricated and manufactured homes as affordable housing solutions. As part of the initiative, the city revised its zoning regulations to distinguish manufactured and modular housing from pre-1976 “mobile homes,” which had long been banned. Previously, manufactured homes were classified under the same category, restricting their placement. The new ordinance now permits manufactured housing within city limits, albeit with a discretionary use permit, paving the way for greater affordability and accessibility in urban housing.

Conclusion

Manufactured homes make up only 5% of the total housing stock but provide an alternative form of housing that meets the needs of various households, particularly in rural areas. Although they offer a lower-cost option compared with site-built homes, factors such as an aging housing stock, financing limitations and zoning restrictions could influence their accessibility and long-term viability.

Trends such as the increasing prevalence of multi-section homes and a growing share of units titled as real estate suggest a gradual shift in consumer preferences toward housing options that more closely resemble site-built homes in size, functionality and financing. As housing affordability remains a key concern, manufactured homes continue to play a role as an affordable supply in the broader housing landscape, and expanding their use through education, innovation and zoning reform could improve access to cost-effective housing.

Footnotes:

Discover more from Eye On Housing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.