Over the past 125 years, women have played a crucial and multifaceted role in the labor force. Increasing women’s participation in the workforce is not only essential for individual and family well-being, but also contributes significantly to overall labor force participation rates and economic growth by adding more workers and enhancing overall productivity1.

Historically, women’s labor force participation rate rose rapidly between 1948 and 2000, peaking around 60% in 1999. During the same period, men’s participation rates declined. However, since 2000, the growth in women’s labor force participation has flattened and then declined.

According to the March 2025 Employment Situation Summary reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), women’s labor force participation rate held steady at 57.5%, and women now represent nearly half (47%) of the total U.S. labor force.

Selected Categories

Prime-age women (ages 25-54) represent a significant and growing segment of the U.S. labor force. As of 2024, they accounted for nearly 30% of the civilian labor force, compared to 34% for prime-age men. According to the latest data from the Current Population Survey (CPS), prime-age women had a labor force participation rate of 78%, the highest among all female age groups. This rate has fully recovered from the COVID-19 pandemic, surpassing its previous peak recorded in February 2020.

As discussed in the previous blog, higher levels of educational attainment are strongly associated with higher labor force participation and lower unemployment. Women with a bachelor’s degree or higher have played a vital role in shaping the labor market. In 2024, about 70% of women with this level of educational attainment were active in the labor force, compared to only 34% of women who had not completed high school.

The CPS data also reveals notable differences in women’s labor force participation based on parental status. Women with older children (ages 6 to 17) and no children under 6 years old had a higher labor force participation rate than those with younger children. Interestingly, women without children had a relatively lower labor force participation rate compared to those with children. Further research from the Brookings Institution and The Hamilton Project2 highlights a significant shift: women with young children (under 5 years), especially those who are highly educated, married, or foreign-born, are more likely to be in the labor force now than they were before the pandemic.

Women’s labor force participation also varies by race and ethnicity. Among women ages 16 and over, Black women had the highest participation rate at 61%, followed by Hispanic women (59%), Asian women (59%), and White women (57%).

The figure below reflects the diversity and complexity of women’s roles in the workforce.

Women in Industry

As more women enter the labor force, they are increasingly shaping a broad range of industries–from healthcare and education to leisure and hospitality, retail, technology, and construction.

In 1964, women were primarily employed in a narrower set of sectors. The top four industries employing the most women at that time were: manufacturing; trade, transportation, and utilities; local government; and education and health services3.

By 2024, however, women’s participation in the workforce has expanded significantly, both in scope and impact. According to the latest CPS data, women dominated the education and health services sector, where they hold approximately 27.6 million jobs. That means seven in every ten workers in this field are women. Moreover, women now make up more than half of the workforce in several other key industries, including other services, leisure and hospitality, and financial activities.

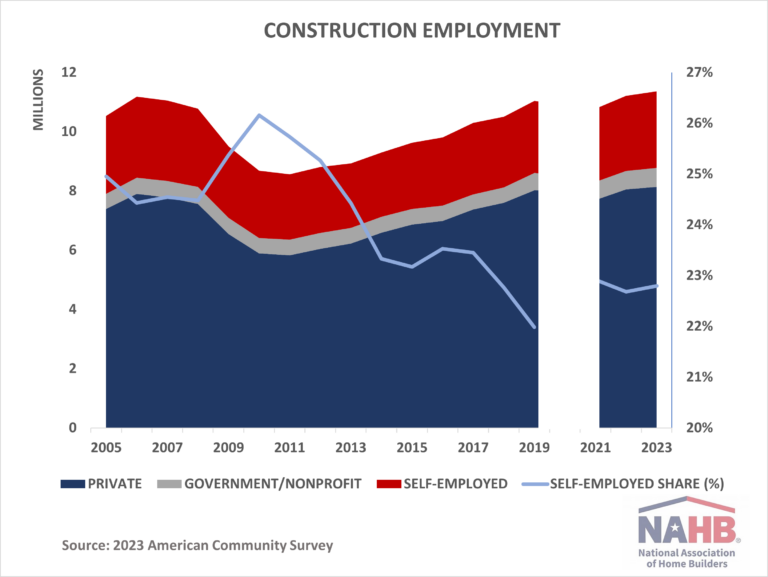

Despite their growing role in the workforce, they remain underrepresented in certain sectors, most notably, construction. Although women now make up a significant portion of the overall labor force, they account for just 11% of total employment in the construction industry. Of those, only 2.8% of women work in actual trade roles, while most women in the industry are employed in:

Office and administrative support

Management

Business

Financial operations

Gender Pay Gap by Occupation

While the gender pay gap in the U.S. has narrowed significantly over the past few decades, it remains a persistent issue in the labor market. According to a study4 by the Pew Research Center, women earned about 65 cents for every dollar earned by men in 1982. By 2023, that figure had risen to approximately 82 cents on the dollar—a clear sign of progress. However, the pace of change has slowed considerably in recent years.

In 2024, the CPS data shows that women working full time earned a median weekly wage of $1,043, compared to $1,261 for men. This means women earned 83 cents for every dollar earned by men—a 17% gender wage gap.

At the occupational level, women earn less than men across all major occupational groups, even ones dominated by women. The smallest gender pay gap was found in community and social services occupations. In contrast, occupations in legal, sales and related, protective services, and production display larger disparities in earnings between women and men.

The Future of Women in the Workforce

Looking ahead to 2033, the number of women in the labor force is expected to continue growing, driven primarily by the prime-age women (ages 25 to 54). BLS employment projections estimate that roughly 3.2 million prime-age women will join the workforce between 2023 and 2033. During this period, their participation rate is projected to increase slightly, reflecting continued momentum in women’s economic engagement.

Meanwhile, the U.S. labor market is experiencing a critical shortage of skilled workers, especially in fields like STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) and skilled trades. As the NAHB Chief Economist stated, “The ultimate solution for the persistent, national labor shortage will be found…by recruiting, training and retaining skilled workers.” This applies equally to the women’s labor force.

Women’s participation is closely tied to their access to education and skills development. As more women pursue higher education and specialized training, their career opportunities expand, particularly in fields previously dominated by men. This progress can help narrow the gender pay gap over time.

However, women often shoulder disproportionate family and caregiving responsibilities, not only during their reproductive years, but throughout their lives. According to the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), on a typical weekday, prime-age working women spent about four hours on caregiving and household tasks, such as household activities, caring for and helping household members, and purchasing goods and services. This is nearly twice the time men spent on the same activities. Many women face a tough decision between career advancement and family caregiving responsibilities, often leading to reduced work hours or even complete withdrawal from the labor force.

To support and increase women’s labor force participation, it may be beneficial to consider a range of policies and workplace reforms. For example, promoting flexible work arrangements can help women better balance professional and personal responsibilities. Narrowing the gender pay gap would also play a critical role in ensuring fair compensation and financial security. Furthermore, expanding access to affordable and high-quality childcare could remove a major barrier for many working mothers. In addition, continued investment in education and training programs would enable women to advance in their careers and contribute to broader, long-term economic growth.

To conclude, empowering women to succeed in the workforce not only improves individual and family well-being, but also strengthens the entire economy.

Note:

Discover more from Eye On Housing

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

This article was originally published by a eyeonhousing.org . Read the Original article here. .