In the first part of this series, we looked at the history of the infamously car-centric American suburb, and the second evaluated their desirability. In this final part, we’ll turn to their fiscal impact and the question of sustainability.

Are the suburbs simply the less dense outskirts of a city, or are they—as their detractors like to say—a Ponzi scheme that’s swamping states and local municipalities with unrepayable debt while leeching off the cities that subsidize them?

Subsidized by the Cities?

The advocacy group Strong Towns is one of the most ardent supporters of urban densification and highlights the town of Lafayette, Louisiana, to make its case that cities unfairly subsidize their suburbs. As they describe it:

“Like most cities, Lafayette had the written reports detailing an enormously large backlog of infrastructure maintenance. At current spending rates, roads were going bad faster than they could be repaired. With aggressive tax increases, the rate of failure could be slowed, but not reversed. The story underground was even worse. That didn’t make sense to Kevin or to the city’s mayor, a guy named Joey Durel.

Joe, Josh, and I interviewed all the city’s department heads and key staff. We gathered as much data as we could (they had a lot). We analyzed and then mapped out all of the city’s revenue streams by parcel. We then did the same for all of the city’s expenses. This was the most comprehensive geographic analysis of a city’s finances that I’ve ever seen completed. When we finished, we had a three-dimensional map showing what parts of the city generated more revenue than expense.”

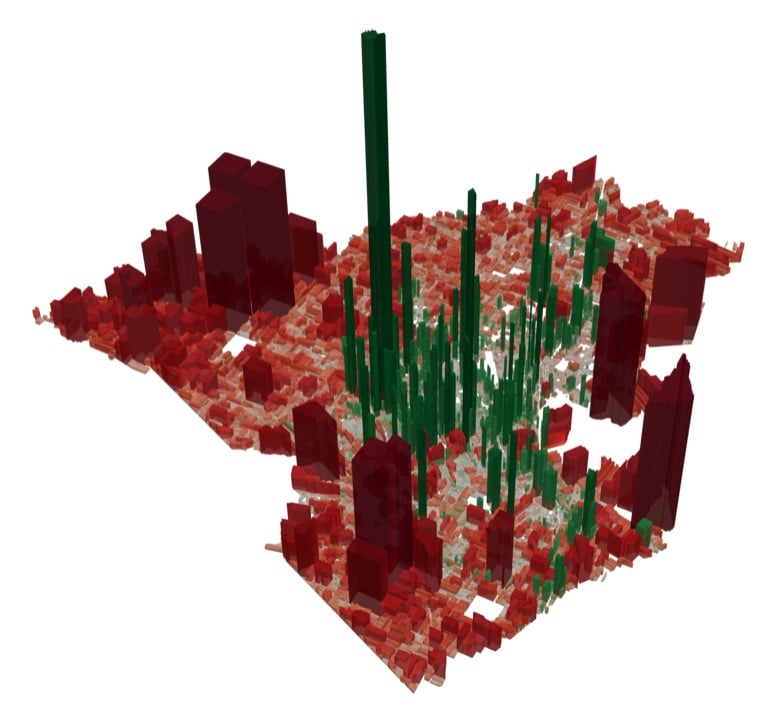

This is the map they came up with:

Green areas bring in money, and red are a net expense. The height of the line shows how much of a net income/expense those areas are.

The article continues:

“The biggest problem that jumped out was that the replacement cost of the city’s infrastructure was $32 billion, while the entire population’s wealth added to only $16 billion! They estimated that the median household would need to pay at least $3,300 a year and as much as $8,000 in taxes just to maintain the infrastructure versus the approximately $150 they were paying.”

We’ll get to the budget shortfalls soon enough. For now, as you can see, the denser urban areas bring in money, while the outlying, less dense (i.e., more suburban) areas cost money.

However, this analysis is clearly skewed, as the downtown area looks like green skyscrapers. Downtowns are often commercial hubs, both in terms of work and retail. They would be net boons even if no one lived there at all, as many people from the suburbs and exurbs travel there to work and shop. Simply densifying the outlying areas wouldn’t change this.

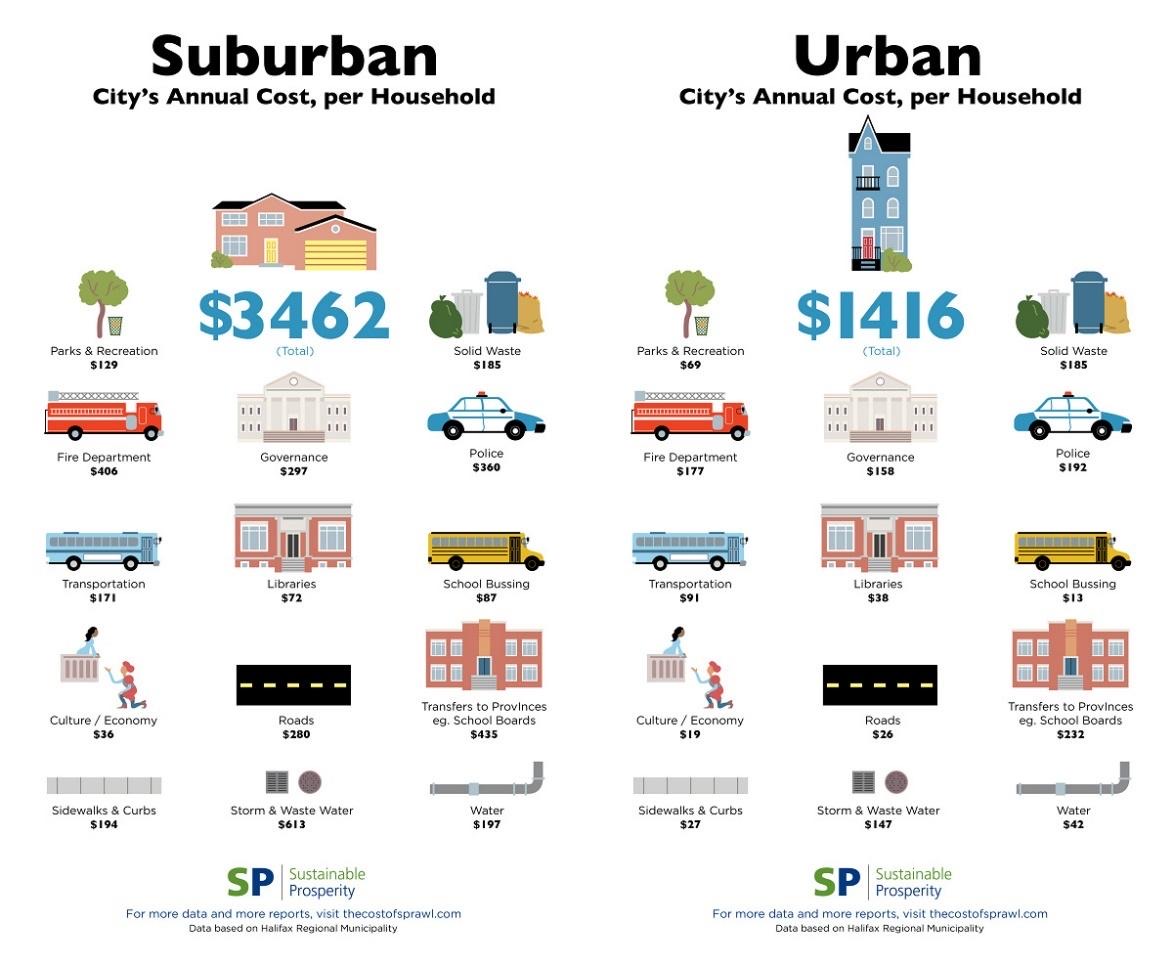

Another analysis from the Canadian town of Halifax provides what I think is a better (and certainly less dramatic) picture. It found that the average annual cost to the city for an urban household was $1,416, compared to $3,462 for a suburban household.

The first thing to note is that the numbers provided by Halifax don’t square with the situation in Lafayette at all. Indeed, the cost of all infrastructure (roads, sidewalks, curbs, water lines, and sewer lines) amounted to $1,284 for suburban properties—not even close to the $8,000 Lafayette supposedly needed. I suspect the Halifax numbers are more representative. After all, our cities have been sprawled for a while now and haven’t completely collapsed.

We should also be very careful about claims about who is subsidizing whom. For example, the Brookings Institute notes, “Today, nearly 60% of all welfare cases can be found in 89 large urban counties,” while TIFs (Tax Increment Financing, a method of subsidizing real estate development) is, as the U.S. Department of Transportation states, “more common in urban areas than in rural areas.”

Other corporate tax incentives tend to be for developments in urban areas as well. For example, the Department of Transportation also notes that of Qualified Opportunity Zones (another tax benefit for development), “38% are in urban tracts, and 22% are in suburban tracts.”

Rural areas have the most Opportunity Zones, but this is still deceiving. After all, in 2018, there were about 151 million people in America’s suburbs and exurbs and only 25 million in the urban cores, which makes the difference per capita in the number of opportunity zones for urban areas versus the suburbs over 10 to 1.

In Kansas City, where I live, the city recently put in a streetcar that (will eventually) go from downtown Kansas City to the popular Plaza area. In other words, it will go from the densest part of the entire metro area to the second-densest part of the metro area. The project received a $20 million federal grant in August 2013 and is seeking $174 million more in federal money to complete.

In other words, in this case, the suburbs are subsidizing the city.

And this is true with almost all public transit other than buses. In 2018, government spending on public transit was $54.3 billion. Speaking of aging infrastructure, it had an over $100 billion maintenance backlog.

But that doesn’t change what seems to be a well-documented fact: Suburban infrastructure is more expensive to maintain than urban. The highlight of this inefficient use of land and the forced subsidization of the suburbs (and rural towns, for that matter) is the town of Backus, Minnesota. As the popular anti-suburb YouTuber Not Just Bikes notes:

“An extreme case is the small town of Backus, Minnesota, which was at the end of life of its wastewater system. But because this town was made up of sprawling, low-productivity, car-centric infrastructure, the wastewater system was sprawling and wasteful as well. The replacement cost was $27,000 per family, which was the median household income of the town.”

Not Just Bikes notes that such towns should have septic systems and wells, not a “sprawling wastewater system.” And it’s hard to argue with that logic. He’s right here.

Indeed, the case for this type of prudence, as well as increasing density where possible and viable, is fairly strong. Obviously, densifying rural farming towns would defeat the purpose of farming, but for the most part, infill is superior to further sprawl. But the case being made is often overstated or even wildly overstated, while the problems causing flight to the suburbs (like the crime issue discussed in Part 2 of this series) get ignored.

There’s also a weird urban bias at play. For example, another popular anti-suburb YouTuber named Alan Fisher has a video with the text on the thumbnail reading “I Don’t Care About the $$$” when it comes to one of the biggest boondoggles in American infrastructure history, namely, California’s high-speed rail project to connect San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Back in 2008, this project was originally envisioned to cost $40 billion in total and be finished by 2020. Well, it’s 2024, the project is now expected to go a cool $100 billion over budget (hopefully, this makes you feel a bit better about your last rehab project), and there really is no end in sight.

So, if we’re going to wag our finger at Backus, Minnesota, what should we make of this farce of a project? And why should taxpayers—both urban and suburban alike—be subsidizing it?

A Ponzi Scheme?

Despite my criticisms of urban activists, the evidence they provide does indicate suburban infrastructure is notably more expensive to maintain than urban infrastructure. Thereby, we should be looking to build denser when possible, even in outlying areas. This would also help alleviate some of the “soullessness” I complained about in Part 2 regarding commercial centers in suburban areas.

But again, the anti-suburb folks take their arguments way too far. In fact, this time, they go overboard, claiming “the suburbs are a Ponzi scheme.” Charles Marohn with Strong Towns explains that the main methods of growth benefit a city immediately “from all the permit fees, utility charges, and increased tax collection… [but] Cities also assume the long-term liability for servicing and maintaining all the new infrastructure, a promise that won’t come fully due for decades.” The second part is the problem, as “the revenue collected over time does not come near to covering the costs of meeting these long-term obligations.”

This is the “growth Ponzi scheme” the car-centric suburbs have created, or more accurately, are the product of. In order for a city to stay solvent with this model, they have to continue to grow until, like with Bernie Madoff and all Ponzi schemes, you can’t get enough growth to finance the costs of the existing infrastructure, and it all comes crumbling down.

Marohn concludes that:

“To financially sustain itself, then, a city or town utilizing the American suburban development pattern and making this tradeoff must believe one of the following two assumptions to be true:

1. The amount of financial return generated by the new growth exceeds the long-term maintenance and replacement cost of infrastructure the public is now obligated to maintain, OR

2. The city will always grow in ever-accelerating amounts so as to generate the cash flow necessary to cover long-term obligations.”

Since the financial return generated by new growth with suburbs does not exceed long-term maintenance costs, for a city to be financially feasible, it must grow forever to stay financially viable; thus, it’s a Ponzi scheme.

This is, however, the exact same mistake that some libertarians make when describing Social Security as a Ponzi scheme. Yes, like a Ponzi scheme, Social Security takes money from investors (or taxpayers, in this case) and pays out their principal to other investors (in this case, retirees). But that’s not enough to make for a good analogy. After all, much of your gut flora and the bubonic plague are both bacteria, so should we assume they’re the same?

A Ponzi scheme is inherently a closed system. The principal from new investors is used to pay the returns of previous investors. Not only that, but the returns need to be high enough to elicit new “investment.” With Social Security, the returns can be reduced to levels below that which the taxpayer put in (and they have been to admittedly paltry levels).

Infrastructure does not need high returns; it just needs to be maintained. Moreover, American infrastructure, like Social Security, is not a closed system. Tax money can be raised from other sectors of the economy to fund it, as has been done to the chagrin of many urban advocates.

Marohn admits this much himself in another piece, where he notes there are four ways American cities finance growth:

- Government transfer payments

- Transportation spending

- Debt

- The growth Ponzi scheme

The first two of these may not be ideal, but they are sustainable.

The state of U.S. infrastructure is quite bad overall. Both the Trump and Biden administrations made infrastructure improvement a key plank of their platform, for good reason. In 2021, the American Society of Civil Engineers released a report concluding that, among other things, 43% of U.S. roadways are in poor or mediocre condition, and the United States faces a $2.59 trillion shortfall in infrastructure needs over the next 10 years.

While this sounds daunting, that amounts to a “mere” $259 billion per year. In 2024, the United States GDP is over $28 trillion, and the government spent an obscene $916 billion per year on “defense,” more than the next top 10 countries combined.

I think we could still defend our country rather easily by cutting that in half. That would pay for all the infrastructure needs without ending the suburbs and still have enough left over to reduce the deficit or cut taxes to boot.

The whole “Ponzi scheme” argument might make for a nice sound bite, but it’s not true and doesn’t help their case. Therefore, the suburbs are not a Ponzi scheme.

Unpayable Debt?

Instead of paying as they go, have American cities relied instead on mountains of debt to maintain their overly sprawled infrastructure each time it requires an overhaul? As Not Just Bikes puts it:

“The city may get it built for cheap, but the city is ultimately responsible for maintaining that infrastructure forever. The big problem begins if there isn’t enough tax revenue collected to cover the replacement cost of the infrastructure…when you get a couple of generations into the suburban experiment, the maintenance obligations of the past start to catch up with you.”

So what do our cities do? They take on debt.

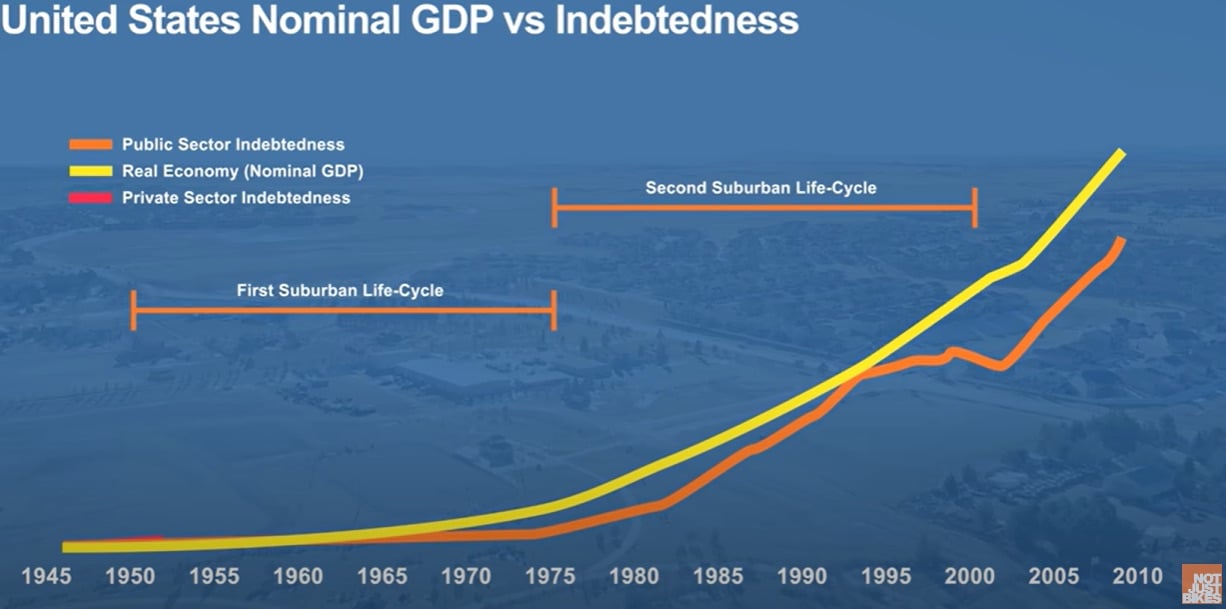

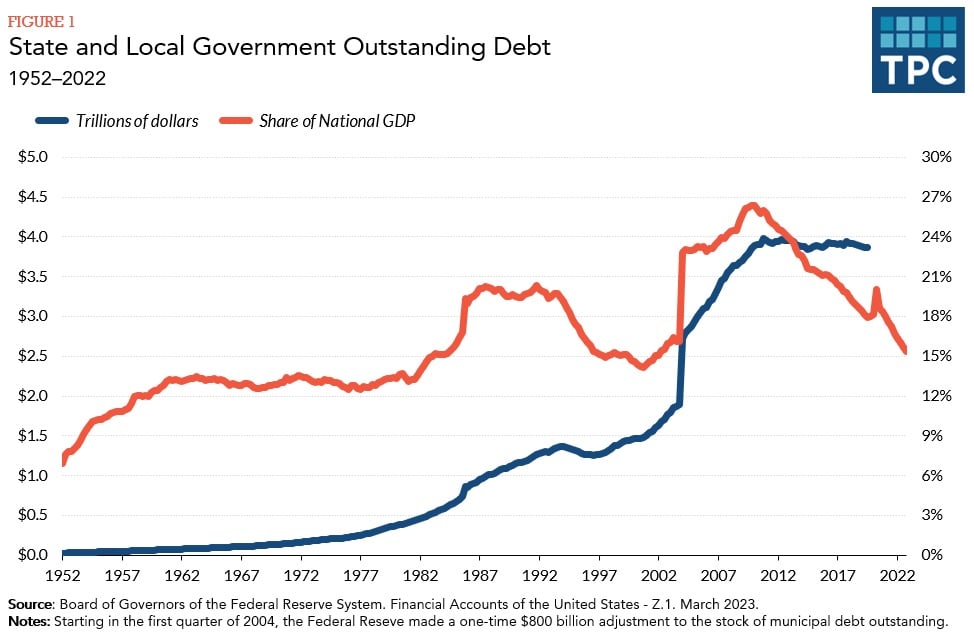

In another video, Not Just Bikes provides this chart to show that public sector indebtedness is highly correlated to overhauling our infrastructure after each life cycle, which is heavily correlated with the nation’s indebtedness.

The argument makes logical sense but doesn’t seem to be backed up by the chart he provides, which shows debt rising at about the same pace and then almost doing the opposite of what anti-suburb activists say it should in 2000 when the “second suburban life cycle” finished.

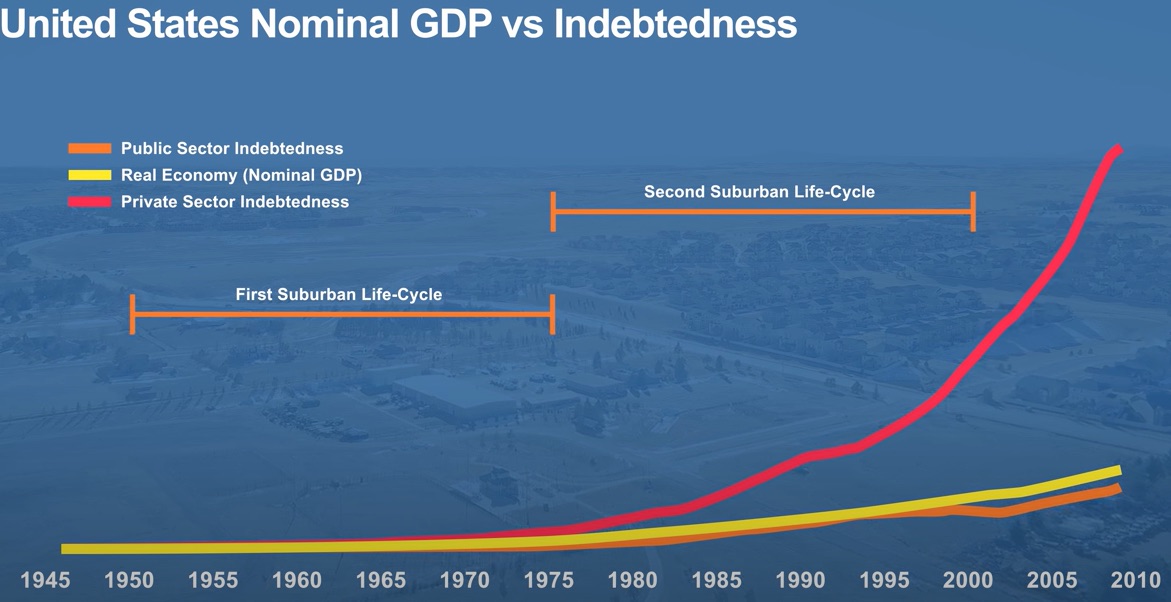

Not Just Bikes then adds private indebtedness to the picture, and it’s ugly. But shouldn’t failing public infrastructure primarily affect public debt, not private?

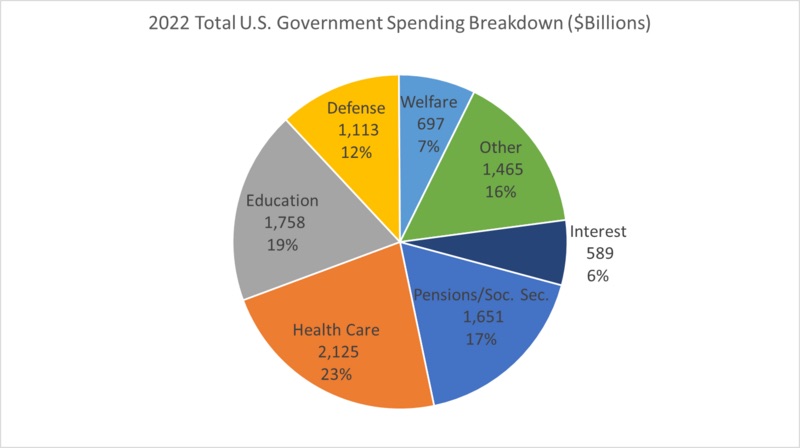

Furthermore, if we look at what the U.S. government spends its money on at the local, state, and federal levels, infrastructure is a relatively small piece of the puzzle.

Infrastructure would fall under “other,” making it substantially less than 16% of public sector spending. In 2017, for example, all levels of government spent $5.6 trillion in total and $309.2 billion on infrastructure and transportation. So 5.48%, to be exact.

Furthermore, while municipal debt has grown to a whopping $4.1 trillion in 2022, it has leveled off over the last decade, and as a percentage of GDP, it has fallen from almost 27% in 2012 to a little over 16% today.

Final Thoughts

It may seem that I have been quite critical of the pro-urban, anti-suburb activists throughout this three-part series. And indeed, many of their claims, from the streetcar conspiracy to the suburban Ponzi scheme, don’t hold water.

Indeed, even comparing American suburbs to European ones is a bit of a red herring. The stereotype of dense, urban European cities with incredible public transportation applies predominantly to its large cities. There are plenty of suburbs in Europe that look rather American, as you can find from any quick Google search.

But there are some good points buried within. Suburban development costs more to maintain than urban development, and it thereby makes sense to build denser when possible. Furthermore, the commercial centers in suburbia are boring, car-dependent monstrosities. Walkable malls seem to have died, but making more walkable “destination points” rather than endless rows of strip malls would be a marked improvement.

Single-use zoning should also be done away with in commercial areas and (at least mostly) replaced with multi-use zoning, which adds vibrancy and prevents commercial zones from going dead and becoming crime magnets at night.

But urban advocates not only exaggerate (sometimes wildly) their claims—they also have important blind spots. The most obvious is crime. Instead, they tend to focus on more coercive methods of preventing suburban sprawl than creating incentives for people to stay in and move to urban areas (like reducing crime). We see this process in things like urban growth boundaries, which often cause real estate prices to increase dramatically and price out the middle class.

Better solutions would include incentives to infill versus building new subdivisions. Recent moves toward allowing property owners to build ADUs (accessory dwelling units) in various cities is a good start.

Overall, suburbia was created predominantly by what the car allowed people to do, not by conspiracies among car manufacturers. And the suburbs have not been a disaster, although it comes with significant downsides.

It’s not unusual for the outlying areas of cities to be substantially less dense than the urban core. While it makes sense to move toward more densification overall, it does not make sense to abandon the suburbs, pack people into pods in dense cities like sardines, or try to phase out the automobile with various coercive methods.

Note By BiggerPockets: These are opinions written by the author and do not necessarily represent the opinions of BiggerPockets.